News

News

The Abbey and the First World War

A number of articles have appeared on local history Facebook pages in the last weeks concerning the First World War, and local participation in it. Questions about the Abbey and the Great War have encouraged us to post the following article.

On August 1st 1914, the day after Germany had declared war on Russia, the French Government mobilised its armed forces. Two days later the German ambassador in Paris delivered a note to the French authorities indicating that a state of war existed between their countries. On 4th August, England declared war on Germany.

The monks of Farnborough found themselves in a strange situation. As a result of anti-clericalism in France, the Laws of Associations, and the separation of Church and State, the monks were living in England in exile. When it came to the War however the monks were bemused when their call-up papers arrived in the post. Abbot Cabrol quipped, ‘So we are not welcome to live in France, but they do not mind us dying for France!’

To its credit, the community was quick to respond to the mobilisation order. Dom Gougaud, Pères Godu, Cabassut and Perret, and Frère Savignac left the Abbey on August 3rd. They were followed shortly by Dom Wilmart. Two older men, Dom Villecourt and Brother Francis Belbech, had to report to the French consulate but were not immediately required for service. Dom Dumaine and Père du Boisrouvray, although previously declared unfit for military service (du Boisrouvray’s eyesight had cut short an illustrious military career at St Cyr), were required to go to the consulate at Southampton for a further examination. This resulted in a renewal of their exemption.

Brother Joseph Becker, the German lay-brother, had to register with the local authorities. At the age of eighty he was not considered to be an immediate threat to the future of the British Empire, but was not allowed to travel outside a five-mile radius of Farnborough!

Dom Cabrol was in France when war was declared, assisting at the twenty-fifth Eucharistic Congress held in Lourdes. Dom Debroise was also in France preaching a retreat, and Frère Alphonse Descourtieux was with his family in Limoges. Because all the trains had been commandeered for troops, the three were delayed and not back home till some weeks later. It is evident that movement cannot have been too restricted since Cabrol spent three weeks on the continent in March of 1915, and was in France in early 1916, and again in September of that year. In 1917 he was off again on his travels, crossing to France on April 9th and leaving for Silos in Spain for the election of a new abbot, returning home after three months. Dom Cottineau had been in Rome with the Vulgate Commission. He travelled to Farnborough and back to Rome in the summer of 1915. In October of 1915, Dom Emile Debroise went off to Mont Saint Michel to take up his post as chaplain to the pilgrims and Dom Paul Serrant went off teaching in Angers, returning in August of the following year.

Dom Bertini was professed in 1908 and was at Quarr for studies from 1910 to 1913, always coming back home for holidays. He was ordained, in fact, at Quarr in April of 1913. He had gone to the Abbey of Clairvaux in Luxembourg in June 1914, and when war was declared, had gone to Einsiedeln in Switzerland on the first stage of his journey home. He had hoped to move south to Italy, but complications arose because, as an Italian national, he had not done military service. Though born in Italy, he had never lived there. Permission to go to Italy came from an unexpected source. The King of Italy granted an amnesty to all ‘deserters’ on account of the birth of his daughter. ‘Thanks to Princess Giovanna, I can go to Italy,’ Bertini wrote home to his family. The new year saw him still at Einsiedeln and not in good health. By mid-March the community at home had heard conflicting reports about him. Cottineau wrote that he had reached Rome and was at Sant Anselmo. Another report however held that he was at Chiari and was being detained by the military authorities till the end of the war. In January of 1916, Bertini was trying, in Rome, to get a permit for England, and evidently succeeded since he came back to Farnborough in March of 1917, having been exempted from military service with the Italian forces through the influence of Cardinal Bourne. Bertini became a naturalised British subject, volunteered to serve as an army chaplain and received orders to join up in May 1917. Dom Bertini served on the Italian Front until September of 1918 when he was sent home on leave to his family in Bournemouth.

In Paris, on his way back to England, he encountered some Italian nuns. In helping them to sort out a problem, he missed his connection. They offered him hospitality for the night and he said Mass for them the following morning. It was to be his last. He arrived at Southampton early on the morning of September 21st. He was undecided as to whether to go to his family or to return to the Abbey and be back for the Patronal Feast. Since the Bournemouth train arrived first he opted for family.

The arrival home at nine o’clock in the morning was a tremendous thrill for his family. It was arranged for him to sing the Missa Cantata at Boscombe the next day, but when that day arrived he was unable to do so. The dreaded ‘Spanish influenza’ had taken hold of him. At first it seemed like a mild attack, but by the end of the week he was delirious and gravely ill. He died at four in the afternoon whilst singing to him self the chants of second vespers of St Michael’s Day. On October 2nd there was a solemn requiem in the parish church and the coffin was taken to the station on a gun carriage covered with the Union Flag. Abbot Cabrol informed the family at Farnborough station that the Bishop (Cotter) had asked to sing the requiem. Again, a military escort led the short distance from the church to the cemetery. Abbot Cabrol said the graveside prayers and there was the customary last post and gun salute. He was thirty-three years old. Just before he died he called his sister to his bedside. He had arranged for her to join the IBVM sisters. Gasping for breath he told her, ‘Mother’s found out and she’s upset. Don’t worry. I’ll see you through!’ She became Sister Barbara at Saint Mary’s, Ascot.

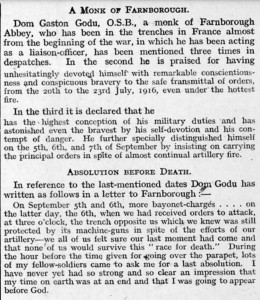

News filtered back from other monks on active service. Père Jean Perret, a twenty-two year old, was captured at the Front in late September of 1914, and was held prisoner at Stuttgart. He eventually returned home in September 1919. Dom Louis Gougaud was taken prisoner and held in Germany. He wrote of his good treatment and the fact that he was permitted to say Mass. He arrived home in March of 1919. Père Gaston Godu had gone as a junior monk to do his two years of military service. Now he was called back and, on active service in France, was ordained to the priesthood in Vannes on November 8th 1914, and so was able to say daily Mass until he went to the Front in mid-December. In July 1915, a note arrived to say that he had been mentioned in the ordre du jour de l’armée; and was awarded the Croix de Guerre. He was safely home by September of 1919.

Frère Georges Savignac was clothed in the habit as a novice on 2nd February 1914, and was killed on 18th February 1915. He was from Toulouse and had studied at the Ecole du Commerce before doing his military service as an infantry officer. He studied for the priesthood under the direction of an abbé with whom he resided in Toulouse. He was brought into contact with a young student of the Ecole des Beaux Arts, Roger Durey, whom he helped to return to the faith. Savignac introduced him to the Abbé Chatelard, chaplain to the Catholic students, and the three of them maintained a close friendship. Durey recognised in Savignac ‘a very delicate soul,’ and acknowledged that ‘he illumined the first stage of my path as the Abbé illumined the second.’

During his novitiate Savignac was remembered as ‘a very charming fellow.’ On August 3rd, 1914, he rejoined the French Army as a Lieutenant of the 59th Infantry Division. Abbé Chatelard received a note from him in November which implied that he was starting for the Front. Roger Durey wrote to Savignac to tell him of his progress towards accepting the Catholic Faith, and the young officer expressed in reply his joy ‘to feel that we are coming nearer and nearer to one another and are both being spurred on towards the same Ideal where we shall only think of losing ourselves.’ His last letter to Durey, dated 6th January 1915, spoke of ‘our lives lit up by the same sun of beauty and our hearts joined together in that furnace of love which is the heart of God.’ Ten days later, Durey went to confession and the next morning made his first Holy Communion.

News of the death of the young novice Savignac was not received till February of 1916, almost a year later. His body had been found some eight months after he had been killed. The High Mass of Requiem was celebrated on the first anniversary of his death. The Empress sent a representative and the French Consul from Southampton was present. Savignac, like Godu, had been mentioned in the ordre du jour, and the community had its second Croix de Guerre.

Père Cabassut was given ten days of leave from the Front in November 1916. These he spent at home in the Abbey. He then returned to France where he remained till his demobilisation on June 1919. Dom Wilmart’s wartime adventures were outlined in the July edition of this review. Dom Villecourt was initially exempted but later called up, in 1916, for military duty. He acted as a medical orderly. He returned home in September of 1919.

Brother Francis Belbech, also exempted at the start of the War, was called up in July 1916. At the age of forty-seven he was the eldest member of the community to be called to the colours, and was the first to return home, arriving on 30th November 1918. Mention ought also to be made of Dom Guthrie who was professed in 1910. He was sent to Quarr for studies, and to the regret, even distress, of the Farnborough community, he decided to make solemn profession to the Abbey of Solesmes. It was a lesson the community would not forget. He died as an army chaplain of wounds on 25th November 1916.

Godu with his medal on the steps of the Abbey Church.

The British fragment of the community was left unbothered until a bill was passed by the government in January 1916 making military service compulsory for single men. For the priest- monks there was no problem but the situation was different for the lay-brothers. Of the three professed brothers, Alban Pickett and Paul Lacey were in their mid-thirties, and Brother Anthony Cooper was twenty-six. Abbot Cabrol attended a London meeting with the heads of the religious orders to discuss the issues, and representations were made to the governments by ecclesiastical authorities on behalf of non-clerics who came under the conscription bill. A prompt decision was made by the government not to give them exemption. But they were not conscripted. As the War progressed and the toll of casualties mounted, the French military draft regulations were reassessed. In March 1917, it looked as if Dumaine and du Boisrouvray would be called up after all. They were, however, examined in London by a conseil de revision at the end of April and exemption was confirmed for both of them. There was a nervous moment in April 1918 when it was feared that a new military service bill would result in clergy being called to non-combatant roles. The clause concerning the clergy was later withdrawn.

Dom Gâtard’s services were used by the French Red Cross. He was taken on an official visit to France at the end of May 1917 in order to gain eye-witness impressions at the Front in order to make a tour of Ireland to raise funds for the wounded French soldiers. He journeyed to Ireland twice for this purpose.

Monasteries in Belgium found themselves in the German war path. Dom Conway records in this dairy for 17th October 1914; ‘A Louvain monk arrived today. He was dressed in a most extraordinary manner and had practically no luggage. His name is Dom Vincent.’ Within a few days five young monks from the Abbey of Saint André in Bruges arrived. Of these the diarist exclaimed; ‘they wore grey trilby hats…and very light grey it was too!’ A month later two more arrived from Bruges. At Christmastide these went to Quarr to study philosophy, except for Dom Edouard who remained to study theology. He was ordained subdeacon by Bishop Cotter on 29th May 1915 and went on military service in July, with the Belgian forces. A Scheut missionary Père Henri de Vries, passed nine months here trying to find an opportunity to travel to Inner Mongolia where his community had flourishing missions. When he left in August 1915, he left a note in the guest book to the effect that the community had treated him ‘si charitable comme un confrère’ The last refugee was Dom Donatien of Steenbrugge who came in February of 1916 and remained for some time.

On the eve of the War the community had acquired a property called Farnborough Court. The gates opposite the doctor’s surgery are the only reminder of it today. In October of 1914 twenty-five wounded Belgian soldiers were moved in for medical care. They were well looked after by the monks. Later on, British soldiers were also accommodated.

The Empress Eugénie was extremely distressed by the War. She knew what it was like for a mother to lose a son and she could not bear to think of the suffering the death toll was causing. She turned Farnborough Hill into a hospital for officers, mostly Belgian, since the French government objected to French officers being lodged at her home. For her efforts to help the wounded she was made a Dame Grand Cross of the British Empire. Abbot Cabrol was awarded the OBE for his contribution to the War effort.